News

Jesus’ ministry has a very low-key start in John’s gospel. In Mark he silences a demon, in Matthew he teaches a vast crowd, in Luke he preaches in the synagogue but in John 1:29-42, he just stops and talks to a couple of people, asking them what they want, what it is that they, that we, are seeking? What is it that we need?

There are parallels with the way in which the suffering servant, in Isaiah 49:1-7, starts with the needs of others. Whether the servant refers to an individual or to a wider group of God’s people the answer to their own suffering and seeking is to be found in serving others.

The two disciples respond to Jesus with a question of their own: where can we find you? Jesus’ reply, come and see, is an invitation. In the other three gospels Jesus begins his ministry with an action or a statement which shows others who HE IS but here, in John, he invites us to join him so that we might discover who WE ARE.

Just as the people of God who have suffered exile and defeat in Isaiah are offered healing and restoration through engaging in the needs of those around them; so Jesus invites us to find what we seek by participating in God’s work of healing and restoring the world around us.

Who do we think we are? Epiphany is the season of revelation; the stories that reveal Christ’s true nature also reveal our own identity as his siblings in the family of God. Today, as we mark the baptism of Christ we remember that we too are baptised in the same spirit.

In our gospel, Matthew 3:13-17, John does not want to baptise him, yet Jesus insists so that we might not be afraid to follow him into deep waters. Just as the Spirit moved over the waters bringing creation into being, so the spirit moves over the waters of baptism recreating us.

The voice of God calling Christ his beloved child is for us too, we are claimed and renewed and anointed so that we might follow Christ, carrying the spirit of God into the world and working for the renewal of all people and the whole of creation.

The feast of the epiphany tells the story of the magi travelling from the east to pay homage to the Christ child, Matthew 2:1-12. These visitors echo the prophecy of Isaiah 60:1-9 that “nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn” and signal that Christ is a gift, not just to the people of Israel but to all peoples of all nations, faiths and cultures. The gifts they bring speak of the nature of the Christ child: gold for ruling, frankincense for holiness and myrrh for dying.

But this story is not just about Christ’s true nature, it is about ours. At our baptism we too are anointed as leaders, priests and gifts. Just as the gifts given to the infant Jesus symbolise how he will live his life as a gift to God’s world, they show us how we should live. We too are gifted and our gifts are only of any use if they are used for all of us. The prophet Isaiah, 60:1-9 calls us to “arise, shine for your light has come”. The light that shines on us is to become the light that shines from and through us. In sharing this light we lighten the path that leads to a home for all God’s people.

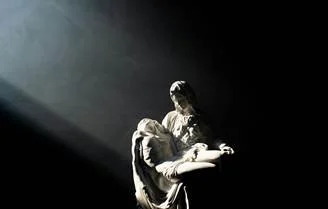

Just four days ago the angels were proclaiming glory to God in the highest and peace to his people on earth, yet today we hear mothers weeping over the death of their children. Had anything changed in the time between the mothers weeping in Jeremiah 31:15-17 and those still weeping in Matthew 2:13-23? Has anything changed since? Mothers’ still weep, innocents are still slaughtered, did Christmas change anything?

The long story of salvation records violence breeding yet more violence: the Israelite children were slaughtered by Pharoah; their freedom was bought by the slaughter of the Egyptian children; they used their freedom to slaughter yet more children, this time Canaanites. When Christ is born Herod slaughters the infants in Bethlehem and Mary and Joseph flee to Egypt, the land of their enemies, and find refuge there. But, something has changed: when Christ returns from Egypt he does not answer violence with yet more violence, instead he submits to the violence of the world to reveal to us a power stronger than violence, the power of love.

Christ’s birth and death and resurrection reveal to us that violence does not come from God and is never sanctioned by God. What God offers us in Christ is the chance to be changed, to become children of God. So that we might receive a power far greater than violence, the power of love. Love is the only power strong enough to defeat violence. Love is the only power great enough to transform an enemy into a friend.

On Sunday 21st December at 6.30pm, make a bee line for church for a traditional service of lessons and carols.

There is no better way to be reminded of the importance of the Nativity than through this familiar selection of readings and music.

This morning, on the last Sunday of Advent, both Joseph and Ahaz receive a sign from God. Signs give us strength and hope, they show us that we are on the right path. The sign given to king Ahaz in Isaiah 7:10-26 is the same as the sign given to Joseph in Matthew 1:18-25, a newborn child. King Ahaz rejects the sign. He is going into battle he wants a sign of power and might. He wants to know that God will strengthen his army and grant him victory, he wants a sign of power and might. The child is a sign of vulnerability and need.

The sign God gives points towards a choice: we can, like Ahaz, focus on securing our position in the world, we can seek to negotiate with power, to ally ourselves with the rich and the mighty. Or, like Jospeh, we can choose to ally ourselves with the most vulnerable.

We too want a sign, a sign that everything will turn out alright, for ourselves and our families, for our community and our nation, for the world. The sign God sends us to follow is still the same: a child, a vulnerable infant. This is the path God points us towards: to stand with the poor, protect the weak, support and uphold those in need. This is the path that leads us to a future all can share.

Are you the one who is to come, or are we to wait for another?” In Matthew 11:2-11, John the Baptist is awaiting execution. In this dark place he wonders whether Jesus is the one who will bring God’s light to the world, the one whom Isaiah 35:1-10 promised when his people were also imprisoned. They both long for a time of freedom and flourishing.

There are times in all our lives when we too question what difference Christ makes to the world when suffering and injustice are still to be seen in every land. Yet Jesus tells us: the blind receive their sight, the lame can walk, the dead are raised to life. We are the blind and lame and dying that Christ heals: he opens our eyes and strengthens our hands in order that we can continue God’s work of healing and liberation.

This Advent the question that John asks, Jesus also asks of us: are we the ones who are to come, or should the world for others?

Today is the second Sunday in Advent, a day when we celebrate the prophets in every generation who call us to a better future. Prophets are not often popular: they insist on telling us things we don’t want to hear; they voice uncomfortable truths; and, most of all, they call us to change. Just so with John the Baptist in Matthew 3:1-12 who warns of “the wrath to come”. He baptises with water but he predicts a baptism of fire. The fire is not punishment for our sins and failings, it is just the inevitable outcome selfish and unethical living, as those living through war and famine and flood know all too well. But the fire of the prophets also offers hope: it burns away all that holds us back to make space for something new to grow and ignites our imaginations so that we can begin to envisage a different future. John calls us to turn around, to turn towards a new future, not on our own but together. As we welcome those to be baptised this morning we remember (and we rejoice) that we are baptised into a community, a community bound together by the fire of the Holy Spirit, the bringer of life. A community charged with reimagining the future. A community called to turn towards that future. A community sent out to live that future into being and bring light and life to the world.